Photo: Green speleothems in the Aven du Mont Marcou (Hérault, France) © Stéphane Pire, Gaëtan Rochez (UNamur)

Speleothems, for instance stalactites and stalagmites, are commonly composed of calcite or aragonite (CaCO3). This mineral compound comes directly from the rock in which the cave was formed and naturally has a white to brownish colour. However, speleothems can sometimes exhibit unique and unusual colours. From yellow to black, blue, red, green, and even purple, there is something for everyone!

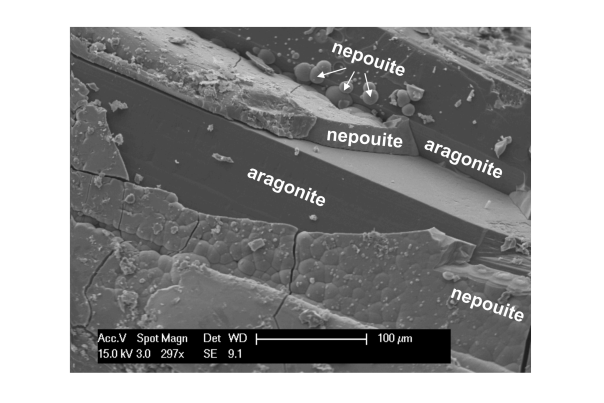

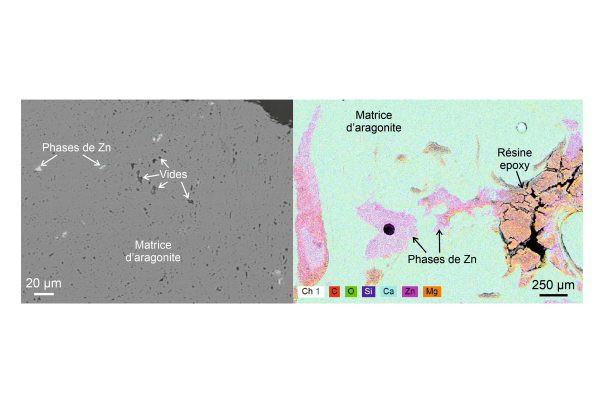

Such a diversity of colours reflects the many possible causes: mineralogical, chemical, biological, or even physical. A speleothem, like any natural formation, is never perfectly pure. Their deposition process, through the precipitation of calcium carbonate dissolved in water, is necessarily accompanied by the deposition of numerous impurities carried along with the water circulating underground. Even if these impurities are sometimes too low in concentration or simply uncoloured, they can still have a visible impact on the colour.

OK, but what is the point?

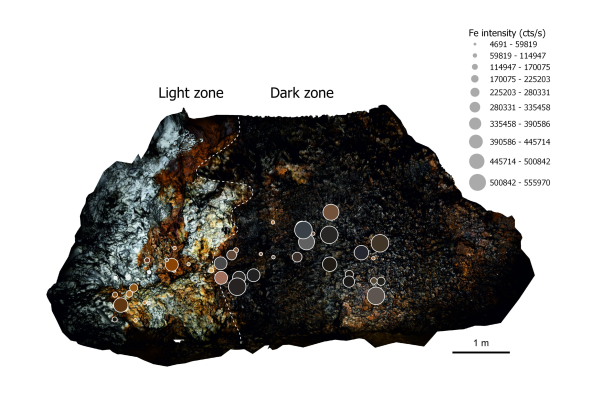

The formation of speleothems is very often linked to impurities dissolved in groundwater. Therefore, studying coloured speleothems provides valuable information about potential contamination of surface water with heavy metals or other harmful organic compounds, which in some cases may be consumed by residents. It is therefore a simple and direct way to identify areas with potentially contaminated water and to determine whether this contamination poses an environmental or health risk.

This is the objective of Martin Vlieghe's thesis: to apply a range of cutting-edge analytical techniques to samples of these speleothems to determine these causes and propose an explanation for the origin of the colouring elements.

Here are a few examples.