Welcome to the Department of Physics!

How can we produce energy without exhausting the planet? What else can space exploration teach us? How can we treat patients more effectively with proton therapy? Artificial intelligence, friend or foe? And how is Schrödinger's cat doing?

You're asking yourself these kinds of questions, and you'd like to be able to answer them. You'd like to understand, know, solve, experiment, test, code, apply. You'd like to make a commitment to preserving the planet, to health, to society. You'd like to take up the challenge of corporate research, or you'd prefer to put your skills at the service of more fundamental knowledge. By joining the Department of Physics at the University of Namur, you will be satiated and we welcome you with enthusiasm.

Find out more about the Physics Department

Spotlight

News

35 years between two accelerators - Serge Mathot's journey, or the art of welding history to physics

35 years between two accelerators - Serge Mathot's journey, or the art of welding history to physics

One foot in the past, the other in the future. From Etruscan granulation to PIXE analysis, Serge Mathot has built a unique career, between scientific heritage and particle accelerators. Portrait of a passionate alumnus at the crossroads of disciplines.

What prompted you to undertake your studies and then your doctorate in physics?

I was fascinated by the research field of one of my professors, Guy Demortier. He was working on the characterization of antique jewelry. He had found a way to differentiate by PIXE (Proton Induced X-ray Emission) analysis between antique and modern brazes that contained Cadmium, the presence of this element in antique jewelry being controversial at the time. He was interested in ancient soldering methods in general, and the granulation technique in particular. He studied them at the Laboratoire d'Analyses par Réaction Nucléaires (LARN). Brazing is an assembly operation involving the fusion of a filler metal (e.g. copper- or silver-based) without melting the base metal. This phenomenon allows a liquid metal to penetrate first by capillary action and then by diffusion at the interface of the metals to be joined, making the junction permanent after solidification. Among the jewels of antiquity, we find brazes made with incredible precision, the ancient techniques are fascinating.

Studying antique jewelry? Not what you'd expect in physics.

In fact, this was one of Namur's fields of research at the time: heritage sciences. Professor Demortier was conducting studies on a variety of jewels, but those made by the Etruscans using the so-called granulation technique, which first appeared in Eturia in the 8th century BC, are particularly incredible. It consists of depositing hundreds of tiny gold granules, up to two-tenths of a millimeter in diameter, on the surface to be decorated, and then soldering them onto the jewel without altering its fineness. So I also trained in brazing techniques and physical metallurgy.

The characterization of jewelry using LARN's particle accelerator, which enables non-destructive analysis, yields valuable information for heritage science.

This is, moreover, a current area of collaboration between the Department of Physics and the Department of History at UNamur (NDLR: notably through the ARC Phoenix project).

How did that help you land a job at CERN?

I applied for a position as a physicist at CERN in the field of vacuum and thin films, but was invited for the position of head of the vacuum brazing department. This department is very important for CERN as it studies methods for assembling particularly delicate and precise parts for accelerators. It also manufactures prototypes and often one-off parts. Broadly speaking, vacuum brazing is the same technique as the one we study at Namur, except that it is carried out in a vacuum chamber. This means no oxidation, perfect wetting of the brazing alloys on the parts to be assembled, and very precise temperature control to obtain very precise assemblies (we're talking microns!). I'd never heard of vacuum brazing, but my experience of Etruscan brazing, metallurgy and my background in applied physics as taught at Namur were of particular interest to the selection committee. They hired me right away!

Tell us about CERN and the projects that keep you busy.

CERN is primarily known for hosting particle accelerators, including the famous LHC (Large Hadron Collider), a 27 km circumference accelerator buried some 100 m underground, which accelerates particles to 99.9999991% of the speed of light! CERN's research focuses on technology and innovation in many fields: nuclear physics, cosmic rays and cloud formation, antimatter research, the search for rare phenomena (such as the Higgs boson) and a contribution to neutrino research. It is also the birthplace of the World Wide Web (WWW). There are also projects in healthcare, medicine and partnerships with industry.

Nuclear physics at CERN is very different from what we do at UNamur with the ALTAÏS accelerator. But my training in applied physics (namuroise) has enabled me to integrate seamlessly into various research projects.

For my part, in addition to developing vacuum brazing methods, a field in which I've worked for over 20 years, I've worked a lot in parallel for the CLOUD experiment. For over 10 years, and until recently, I was its Technical Coordinator. CLOUD is a small but fascinating experiment at CERN which studies cloud formation and uses a particle beam to reproduce atomic bombardment in the laboratory in the manner of galactic radiation in our atmosphere. Using an ultra-clean 26 m³ cloud chamber, precise gas injection systems, electric fields, UV light systems and multiple detectors, we reproduce and study the Earth's atmosphere to understand whether galactic rays can indeed influence climate. This experiment calls on various fields of applied physics, and my background at UNamur has helped me once again.

I was also responsible for CERN's MACHINA project -Movable Accelerator for Cultural Heritage In situ Non-destructive Analysis - carried out in collaboration with the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN), Florence section - Italy. Together, we have created the first portable proton accelerator for in-situ, non-destructive analysis in heritage science. MACHINA is soon to be used at the OPD (Opificio delle Pietre Dure), one of the oldest and most prestigious art restoration centers, also in Florence. The accelerator is also destined to travel to other museums or restoration centers.

Currently, I'm in charge of the ELISA (Experimental LInac for Surface Analysis) project. With ELISA, we're running a real proton accelerator for the first time in a place open to the public: the Science Gateway (SGW), CERN's new permanent exhibition center

ELISA uses the same accelerator cavity as MACHINA. The public can observe a proton beam extracted just a few centimetres from their eyes. Demonstrations are organized to show various physical phenomena, such as light production in gases or beam deflection with dipoles or quadrupoles, for example. The PIXE analysis method is also presented. ELISA is also a high-performance accelerator that we use for research projects in the field of heritage and others such as thin films, which are used extensively at CERN. The special feature is that the scientists who come to work with us do so in front of the public!

Do you have a story to tell?

I remember that in 1989, I finished typing my report for my IRSIA fellowship in the middle of the night, the day before the deadline. It had to be in by midnight the next day. There were very few computers back then, so I typed my report at the last minute on one of the secretaries' Macs. One false move and pow! all my data was gone - big panic! The next day, the secretary helped me restore my file, we printed out the document and I dropped it straight into the mailbox in Brussels, where I arrived after 11pm, in extremis, because at midnight, someone had come to close the mailbox. Fortunately, technology has come a long way since then...

And I can't resist sharing two images 35 years apart!

To the left, a Gold statuette (Egypt), c. 2000 BC, analyzed at LARN - UNamur (photo 1990) and to the right, a copy (in Brass) of the Dame de Brassempouy, analyzed with ELISA - CERN (2025).

The "photographer" is the same, so we've come full circle...

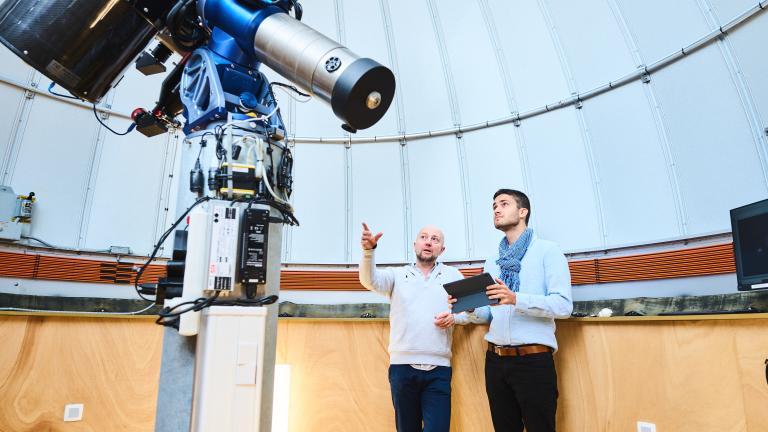

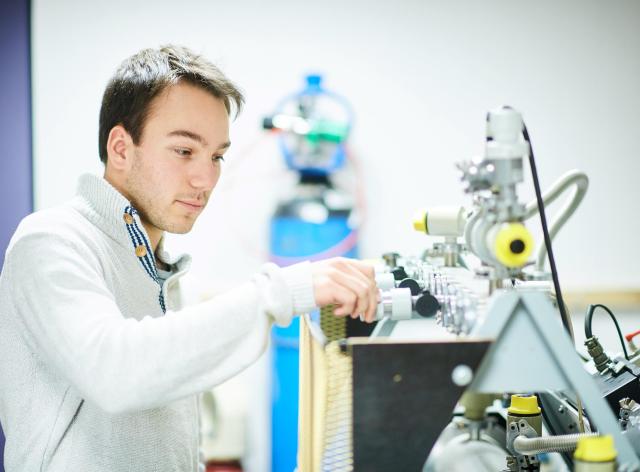

The proximity between teaching and research inspires and questions. This enables graduate students to move into multiple areas of working life.

Come and study in Namur!

Serge Mathot (May 2025) - Interview by Karin Derochette

Further information

- The CERN accelerators complex

- The Science Portal, CERN's public education and communication center

- Newsroom - June 2025 | The Departement of physics hosts a delegation from CERN

- Newsroom and Omalius Alumni article - September 2022 | François Briard

CERN - the science portal

This article is taken from the "Alumni" section of Omalius magazine #38 (September 2025).

UNamur in South America

UNamur in South America

South America is a subcontinent rich in natural and cultural resources. Between biodiversity preservation and development cooperation, UNamur maintains valuable partnerships to address the challenges of biodiversity loss and understand current socio-economic transformations. Immersion in Ecuador and Peru.

Strategically located at the intersection of the Andes mountain range, the Amazon rainforest, and the Galápagos Islands (made famous by a certain Charles Darwin), Ecuador is a hotspot of biodiversity. More than 150 years after the naturalist's observations, this country remains a popular field of study for scientists investigating how wild organisms adapt to changes in their environment.

Ecuador as an open-air laboratory

As part of a two-year project funded by the ARES International Cooperation Commission (ARES-CCI), Professors Frédéric Silvestre and Alice Dennis from the Environmental and Evolutionary Biology Research Unit (URBE) at UNamur have formed a partnership with the Universidad Central Del Ecuador. The goal? To apply the genetic and epigenetic techniques developed in the Namur laboratories to fish and macroinvertebrates in Ecuadorian streams.

"Genetic and epigenetic marks on genes provide valuable information about the environmental stresses experienced by wild populations."

An initial sampling campaign was conducted this summer, and another is planned for next spring, with Frédéric Silvestre and Alice Dennis participating. This collaboration also enabled URBE to welcome an Ecuadorian researcher who came to train in nanopore sequencing techniques, used in this project, and to carry out tests on samples of the species studied. Nanopore sequencing is a method of sequencing long DNA strands using an electrical signal. "This technique is very advantageous because it facilitates genome assembly and allows us to work on both the DNA sequence and its modifications. Nanopore sequencing also uses very small, portable equipment that is easy to use in the field," the researcher continues. The aim of using this technology is to demonstrate the feasibility of this process and, ultimately, to contribute to the development of more effective biodiversity conservation policies based on concrete genetic data.

Peru: Understanding the dynamics of a country undergoing rapid change

Newly appointed Vice-Rector for International and External Relations at UNamur, Stéphane Leyens is involved in no fewer than four projects in Peru, working closely with the Universidad Nacional San Antonio Abad del Cusco (UNSAAC). Located in the Andes mountain range at an altitude of nearly 3,500 meters, this university has been receiving support from the ARES International Cooperation Commission (ARES-CCI) since 2009 to improve the quality of its teaching and strengthen its research capabilities. These projects are set against the backdrop of the new "university law," which has profoundly changed the landscape of higher education by emphasizing teacher training and the social responsibility of universities, which are now encouraged to integrate issues such as interculturality, the environment, and gender into a local rural development perspective.

It must be said that the country's cultural, political, and socioeconomic context is undergoing profound change. As a result, rural communities are torn between their attachment to traditional lifestyles and the appeal of the economic opportunities offered by the modernization of agriculture or the growth of tourism.

It is this tension that Stéphane Leyens is studying in the district of Ocongate (department of Cuzco), located on the route of the Southern Interoceanic Highway. "This paved road, connecting Lima to Sao Paulo and completed in 2006, has completely transformed the community and socio-economic dynamics of the Quechua populations of the high Andes, providing access to the mines of the Amazon, urban markets, higher education institutions, and opening up the region to tourism. The idea was therefore to study this change in dynamics through the prism of family and community decision-making, with a particular focus on education, agricultural activities, and gender issues," explains Stéphane Leyens. These questions—which particularly resonate with the realities experienced by the population—led to two doctoral research projects conducted by Peruvian researchers.

In the same vein, and in a brand new project, the researcher is looking at the impact of the development of informal mining operations on the local economy from an original angle: Quechua epistemology. This project is based on a partnership with a team from the Universidad Nacional José María Arguedas (UNAJMA), which specializes in this approach.

"The rise of informal mining has destabilized family dynamics, with mining activities becoming increasingly male-dominated and agricultural work increasingly female-dominated within communities. To analyze these changes, we start from the framework of thought of the Quechua-speaking farming communities: their mythologies, their conceptions of their relationship to the land and nature, to the community, etc."

Feedback from a student

"As part of the Master's degree in physics, we are required to do an internship in Belgium or elsewhere. I chose to fly to Brazil because local researchers are conducting research related to my thesis topic. It was also an opportunity to step out of my comfort zone and experience life in a distant country.

It went very well, both academically and personally. I had the opportunity to help write an article and follow the entire publication process. The work was very loosely organized, and I was able to conduct my research independently. I quickly formed lasting friendships, particularly by participating in forró classes, a Brazilian dance.

If I had one piece of advice to give, it would be: go for it! Going far away can be scary, but it teaches you a lot, especially the fact that you are capable of bouncing back in sometimes unpredictable situations."

- Thaïs Nivaille, physics student

This article is taken from the "Far away" section of Omalius magazine #38 (September 2025).

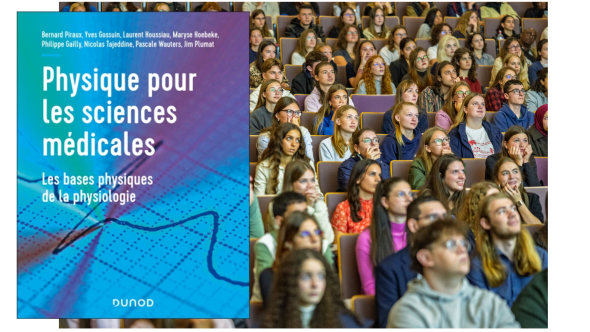

"Physics for medical sciences": a reference book to support students throughout their studies

"Physics for medical sciences": a reference book to support students throughout their studies

Initiated and coordinated by Bernard Pireaux (UCLouvain), this collective work - co-authored in particular by Professors Laurent Houssiau and Jim Plumat (UNamur) - offers a reference manual to accompany students of medicine, biomedical sciences and life sciences throughout their course. Designed as a clear, progressive and practical tool, it illustrates just how essential physics is to the understanding of living organisms and to medical practice.

In France, as in Belgium, medical students generally receive little teaching in physics during their course of study. This situation has its roots in history: until the XIXᵉ century, vitalism - a scientific current that originated in the XVIIIᵉ - postulated that living beings were animated by a "vital force" that escaped physical and chemical laws. Gradually, this vision gave way to mechanism, which asserted that even the most complex biological phenomena obeyed the same universal laws as inanimate matter. This transition marked a decisive stage in the history of science, consecrating the fundamental role of physics in the understanding of the living.

It is in this spirit that the book Physics for Medical Sciences, coordinated by Bernard Pireaux, Professor of Physics at the Catholic University of Louvain, is set. A genuine training tool, it brings together all the essential physics concepts useful to students of medicine, life sciences or biomedical sciences.

Clear, ambitious objectives

- Reconcile students with physics by emphasizing its central role in the health sciences.

- Initiate students from the very beginning of their course with the fundamental laws of physics, which are essential to their training.

- In-depth understanding of the physical mechanisms underlying physiological phenomena, right down to their cellular dimensions.

- Modeling more complex physiological systems.

- Support students throughout their course of study, and even beyond.

Over a year of collaborative work

With over 600 pages, this book is much more than a simple syllabus: it aims to be a veritable "bible" of physics applied to the medical sciences. Its writing mobilized several teacher-researchers for over a year.

At UNamur, two physics professors played a key role:

- Jim Plumat, Professor of Physics Emeritus at UNamur, signed chapter 11 devoted to light, the eye and vision.

This book is a reminder that physics is not a cold, abstract science, but an essential key to understanding and caring for the living. It's a genuine invitation to rediscover the beauty of the link between matter, life and medicine.

- Laurent Houssiau, Professor of Physics at UNamur, wrote Chapters 2 and 3 on kinematics and dynamics, and contributed to Chapter 4 on deformable solids.

With 25 years' experience teaching physics to medical students, he explains:

It's a real challenge to teach physics to medical students. I love it and have been doing it every year for 25 years. I know their problems and their questions, which I've learned through contact with them. And every year is different, which also allows me to learn new things.

Based on concrete medical examples and clearly oriented towards medical physics, the book offers a progressive and pragmatic approach. As Laurent Houssiau points out:"This book is perfectly suited to our students of medicine, biomedical sciences and pharmaceutical sciences, as all its authors have written it in the same spirit."

An innovative teaching approach

Designed as a genuine biophysics course, the book is aimed at French and Belgian medical students as well as those enrolled in life and health sciences programs. Each chapter features:

- an introduction to situate and contextualize the subject,

- many exercises and corrected MCQs,

- one or more medical case studies, particularly in physiology.

The project represents a first in the field. With this publication, students finally have a solid reference tool tailored to their needs, to better understand the physical basics essential to medical practice.

Medical studies at UNamur

Manipulating light to revolutionize quantum computing

Manipulating light to revolutionize quantum computing

Two researchers from the University of Namur's Department of Physics, Professor Michaël Lobet and his PhD student Adrien Debacq, are taking a close look at a subject that fascinates the scientific community : superradiance in media with a refractive index close to zero. In an article published this summer in Nature's prestigious journal Light: science & applications, in collaboration with Harvard University (USA), Michigan Technological University (MTU) and Sparrow Quantum, they contribute to the development of quantum computing.

For the past twenty years, a physical phenomenon has been attracting the attention of scientists over the world: superradiance in media with refractive indices close to zero. Among them, Michaël Lobet, professor at the Physics’ Department of UNamur, FNRS research associate and associate at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). “This is one of the major areas I've been studying for ten years now, and for which I was a post-doctoral fellow in Professor Eric Mazur's team at Harvard”, explains Michaël Lobet.

Superradiance, is a phenomenon that has been known for over half a century. It was theorized mathematically as early as 1954 by Robert Dicke, who showed that when elements such as atoms interact, they can synchronize to emit more powerful light. A bit like a choir singing in unison, the sound produced is much louder than each voice taken separately. But for doing this, the emitters must be very close to one another.

A index that changes everything

Scientists have discovered that one element can change everything: when the emitters are immersed in a material with a refractive index close to zero, rather than in vacuum, the position of the emitters is no longer an issue. The refractive index is a quantity that describes the behaviour of light in a material. In an ordinary material, light behaves a little like waves on the sea: it moves forward, forming crests and troughs that shift. But in a near-zero index medium, it's as if the sea becomes perfectly flat, with no waves, and starts moving up and down in a block. Everything moves in unison: the sea becomes uniform, and the wave stretches to infinity.

When the light field becomes more uniform, all the atoms find themselves optically close to each other, even if they are spatially distant. In other words, the "ambient" near-zero refractive index relaxes the strict distance between the atoms' positions, an essential condition for the entanglement of quantum particles. Quantum entanglement corresponds to correlations between particles, essential for the development of information and quantum computers.

From electrodynamics to quantum computing

This is where the promising contribution of a team of researchers from UNamur, Harvard and Michigan Technological University (MTU) comes in, supported by Dr. Larissa Vertchenko, from Danish quantum technology company Sparrow Quantum. Adrien Debacq, FNRS aspirant researcher at the Namur Institute of Structured Matter (NISM) and co-author of the paper, assisted by Harvard PhD student Olivia Mello and Dr Larissa Vertchenko, have together theoretically developed a photonic chip capable of radically improving the range of entanglement between transmitters, up to 17 times greater than in a vacuum. The emitters were made from nitrogen vacancy (NV) diamonds, structures well known in quantum optics.

This is the first time that such a long range has been achieved using a compact system that can be easily implemented in photonic chips

“This paper shows how near-zero refractive index photonics can transition from classical electrodynamics to the quantum regime, since superradiance is intrinsically quantum.”, summarizes Eric Mazur, Professor at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, who has been at the forefront of these innovative materials for the past decade. Entanglement, another purely quantum property, enables the transfer of quantum information, a concept already raised by Einstein in the 1930s as part of his work on quantum mechanics. The present work is part of this continuation, and more generally of the “second quantum revolution”, which aims to build on the fundamental discoveries of Einstein and the other founding fathers of quantum mechanics.

Very concrete applications

This prospect confirms the nascent research in recent years to potentially revolutionary applications: more efficient lasers, more sensitive optical sensors and, above all, faster and ultra-secure telecommunication tools, thanks to quantum computers. Cybersecurity, for example, is about to be revolutionized by these discoveries, guaranteeing message security through physical laws rather than complex calculations.

Preserving the high degree of entanglement on chip over longer ranges may raise the possibility of multipartite entanglement involving many qubits useful for e.g., the construction of cluster states—important resource for universal one-way quantum computing—as well as large-area distributed quantum computing and quantum communication networks that may offer drastic increase on the computational and channel capacity.

Together with Dr. Seth Nelson, Güney has helped to study the dynamic response of the quantum system in the presence of a pump laser beam.

The challenge for future research is to transform this theoretical project, combining analytical models and numerical simulations, into concrete experimental realizations. The aim is to get a little closer to practical quantum systems, which fit into dimensions as small as the thickness of a human hair. Who knows, maybe one day we'll have a quantum computer in our pocket?

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank the Department of Physics and the NISM Institute, the FNRS for funding the research mandates of Michaël Lobet and Adrien Debacq, and the PTCI technology platform, whose supercomputers made this study possible, as well as for funding in part by the United States Army Research Office under MURI grant (W911NF2420195).

35 years between two accelerators - Serge Mathot's journey, or the art of welding history to physics

35 years between two accelerators - Serge Mathot's journey, or the art of welding history to physics

One foot in the past, the other in the future. From Etruscan granulation to PIXE analysis, Serge Mathot has built a unique career, between scientific heritage and particle accelerators. Portrait of a passionate alumnus at the crossroads of disciplines.

What prompted you to undertake your studies and then your doctorate in physics?

I was fascinated by the research field of one of my professors, Guy Demortier. He was working on the characterization of antique jewelry. He had found a way to differentiate by PIXE (Proton Induced X-ray Emission) analysis between antique and modern brazes that contained Cadmium, the presence of this element in antique jewelry being controversial at the time. He was interested in ancient soldering methods in general, and the granulation technique in particular. He studied them at the Laboratoire d'Analyses par Réaction Nucléaires (LARN). Brazing is an assembly operation involving the fusion of a filler metal (e.g. copper- or silver-based) without melting the base metal. This phenomenon allows a liquid metal to penetrate first by capillary action and then by diffusion at the interface of the metals to be joined, making the junction permanent after solidification. Among the jewels of antiquity, we find brazes made with incredible precision, the ancient techniques are fascinating.

Studying antique jewelry? Not what you'd expect in physics.

In fact, this was one of Namur's fields of research at the time: heritage sciences. Professor Demortier was conducting studies on a variety of jewels, but those made by the Etruscans using the so-called granulation technique, which first appeared in Eturia in the 8th century BC, are particularly incredible. It consists of depositing hundreds of tiny gold granules, up to two-tenths of a millimeter in diameter, on the surface to be decorated, and then soldering them onto the jewel without altering its fineness. So I also trained in brazing techniques and physical metallurgy.

The characterization of jewelry using LARN's particle accelerator, which enables non-destructive analysis, yields valuable information for heritage science.

This is, moreover, a current area of collaboration between the Department of Physics and the Department of History at UNamur (NDLR: notably through the ARC Phoenix project).

How did that help you land a job at CERN?

I applied for a position as a physicist at CERN in the field of vacuum and thin films, but was invited for the position of head of the vacuum brazing department. This department is very important for CERN as it studies methods for assembling particularly delicate and precise parts for accelerators. It also manufactures prototypes and often one-off parts. Broadly speaking, vacuum brazing is the same technique as the one we study at Namur, except that it is carried out in a vacuum chamber. This means no oxidation, perfect wetting of the brazing alloys on the parts to be assembled, and very precise temperature control to obtain very precise assemblies (we're talking microns!). I'd never heard of vacuum brazing, but my experience of Etruscan brazing, metallurgy and my background in applied physics as taught at Namur were of particular interest to the selection committee. They hired me right away!

Tell us about CERN and the projects that keep you busy.

CERN is primarily known for hosting particle accelerators, including the famous LHC (Large Hadron Collider), a 27 km circumference accelerator buried some 100 m underground, which accelerates particles to 99.9999991% of the speed of light! CERN's research focuses on technology and innovation in many fields: nuclear physics, cosmic rays and cloud formation, antimatter research, the search for rare phenomena (such as the Higgs boson) and a contribution to neutrino research. It is also the birthplace of the World Wide Web (WWW). There are also projects in healthcare, medicine and partnerships with industry.

Nuclear physics at CERN is very different from what we do at UNamur with the ALTAÏS accelerator. But my training in applied physics (namuroise) has enabled me to integrate seamlessly into various research projects.

For my part, in addition to developing vacuum brazing methods, a field in which I've worked for over 20 years, I've worked a lot in parallel for the CLOUD experiment. For over 10 years, and until recently, I was its Technical Coordinator. CLOUD is a small but fascinating experiment at CERN which studies cloud formation and uses a particle beam to reproduce atomic bombardment in the laboratory in the manner of galactic radiation in our atmosphere. Using an ultra-clean 26 m³ cloud chamber, precise gas injection systems, electric fields, UV light systems and multiple detectors, we reproduce and study the Earth's atmosphere to understand whether galactic rays can indeed influence climate. This experiment calls on various fields of applied physics, and my background at UNamur has helped me once again.

I was also responsible for CERN's MACHINA project -Movable Accelerator for Cultural Heritage In situ Non-destructive Analysis - carried out in collaboration with the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN), Florence section - Italy. Together, we have created the first portable proton accelerator for in-situ, non-destructive analysis in heritage science. MACHINA is soon to be used at the OPD (Opificio delle Pietre Dure), one of the oldest and most prestigious art restoration centers, also in Florence. The accelerator is also destined to travel to other museums or restoration centers.

Currently, I'm in charge of the ELISA (Experimental LInac for Surface Analysis) project. With ELISA, we're running a real proton accelerator for the first time in a place open to the public: the Science Gateway (SGW), CERN's new permanent exhibition center

ELISA uses the same accelerator cavity as MACHINA. The public can observe a proton beam extracted just a few centimetres from their eyes. Demonstrations are organized to show various physical phenomena, such as light production in gases or beam deflection with dipoles or quadrupoles, for example. The PIXE analysis method is also presented. ELISA is also a high-performance accelerator that we use for research projects in the field of heritage and others such as thin films, which are used extensively at CERN. The special feature is that the scientists who come to work with us do so in front of the public!

Do you have a story to tell?

I remember that in 1989, I finished typing my report for my IRSIA fellowship in the middle of the night, the day before the deadline. It had to be in by midnight the next day. There were very few computers back then, so I typed my report at the last minute on one of the secretaries' Macs. One false move and pow! all my data was gone - big panic! The next day, the secretary helped me restore my file, we printed out the document and I dropped it straight into the mailbox in Brussels, where I arrived after 11pm, in extremis, because at midnight, someone had come to close the mailbox. Fortunately, technology has come a long way since then...

And I can't resist sharing two images 35 years apart!

To the left, a Gold statuette (Egypt), c. 2000 BC, analyzed at LARN - UNamur (photo 1990) and to the right, a copy (in Brass) of the Dame de Brassempouy, analyzed with ELISA - CERN (2025).

The "photographer" is the same, so we've come full circle...

The proximity between teaching and research inspires and questions. This enables graduate students to move into multiple areas of working life.

Come and study in Namur!

Serge Mathot (May 2025) - Interview by Karin Derochette

Further information

- The CERN accelerators complex

- The Science Portal, CERN's public education and communication center

- Newsroom - June 2025 | The Departement of physics hosts a delegation from CERN

- Newsroom and Omalius Alumni article - September 2022 | François Briard

CERN - the science portal

This article is taken from the "Alumni" section of Omalius magazine #38 (September 2025).

UNamur in South America

UNamur in South America

South America is a subcontinent rich in natural and cultural resources. Between biodiversity preservation and development cooperation, UNamur maintains valuable partnerships to address the challenges of biodiversity loss and understand current socio-economic transformations. Immersion in Ecuador and Peru.

Strategically located at the intersection of the Andes mountain range, the Amazon rainforest, and the Galápagos Islands (made famous by a certain Charles Darwin), Ecuador is a hotspot of biodiversity. More than 150 years after the naturalist's observations, this country remains a popular field of study for scientists investigating how wild organisms adapt to changes in their environment.

Ecuador as an open-air laboratory

As part of a two-year project funded by the ARES International Cooperation Commission (ARES-CCI), Professors Frédéric Silvestre and Alice Dennis from the Environmental and Evolutionary Biology Research Unit (URBE) at UNamur have formed a partnership with the Universidad Central Del Ecuador. The goal? To apply the genetic and epigenetic techniques developed in the Namur laboratories to fish and macroinvertebrates in Ecuadorian streams.

"Genetic and epigenetic marks on genes provide valuable information about the environmental stresses experienced by wild populations."

An initial sampling campaign was conducted this summer, and another is planned for next spring, with Frédéric Silvestre and Alice Dennis participating. This collaboration also enabled URBE to welcome an Ecuadorian researcher who came to train in nanopore sequencing techniques, used in this project, and to carry out tests on samples of the species studied. Nanopore sequencing is a method of sequencing long DNA strands using an electrical signal. "This technique is very advantageous because it facilitates genome assembly and allows us to work on both the DNA sequence and its modifications. Nanopore sequencing also uses very small, portable equipment that is easy to use in the field," the researcher continues. The aim of using this technology is to demonstrate the feasibility of this process and, ultimately, to contribute to the development of more effective biodiversity conservation policies based on concrete genetic data.

Peru: Understanding the dynamics of a country undergoing rapid change

Newly appointed Vice-Rector for International and External Relations at UNamur, Stéphane Leyens is involved in no fewer than four projects in Peru, working closely with the Universidad Nacional San Antonio Abad del Cusco (UNSAAC). Located in the Andes mountain range at an altitude of nearly 3,500 meters, this university has been receiving support from the ARES International Cooperation Commission (ARES-CCI) since 2009 to improve the quality of its teaching and strengthen its research capabilities. These projects are set against the backdrop of the new "university law," which has profoundly changed the landscape of higher education by emphasizing teacher training and the social responsibility of universities, which are now encouraged to integrate issues such as interculturality, the environment, and gender into a local rural development perspective.

It must be said that the country's cultural, political, and socioeconomic context is undergoing profound change. As a result, rural communities are torn between their attachment to traditional lifestyles and the appeal of the economic opportunities offered by the modernization of agriculture or the growth of tourism.

It is this tension that Stéphane Leyens is studying in the district of Ocongate (department of Cuzco), located on the route of the Southern Interoceanic Highway. "This paved road, connecting Lima to Sao Paulo and completed in 2006, has completely transformed the community and socio-economic dynamics of the Quechua populations of the high Andes, providing access to the mines of the Amazon, urban markets, higher education institutions, and opening up the region to tourism. The idea was therefore to study this change in dynamics through the prism of family and community decision-making, with a particular focus on education, agricultural activities, and gender issues," explains Stéphane Leyens. These questions—which particularly resonate with the realities experienced by the population—led to two doctoral research projects conducted by Peruvian researchers.

In the same vein, and in a brand new project, the researcher is looking at the impact of the development of informal mining operations on the local economy from an original angle: Quechua epistemology. This project is based on a partnership with a team from the Universidad Nacional José María Arguedas (UNAJMA), which specializes in this approach.

"The rise of informal mining has destabilized family dynamics, with mining activities becoming increasingly male-dominated and agricultural work increasingly female-dominated within communities. To analyze these changes, we start from the framework of thought of the Quechua-speaking farming communities: their mythologies, their conceptions of their relationship to the land and nature, to the community, etc."

Feedback from a student

"As part of the Master's degree in physics, we are required to do an internship in Belgium or elsewhere. I chose to fly to Brazil because local researchers are conducting research related to my thesis topic. It was also an opportunity to step out of my comfort zone and experience life in a distant country.

It went very well, both academically and personally. I had the opportunity to help write an article and follow the entire publication process. The work was very loosely organized, and I was able to conduct my research independently. I quickly formed lasting friendships, particularly by participating in forró classes, a Brazilian dance.

If I had one piece of advice to give, it would be: go for it! Going far away can be scary, but it teaches you a lot, especially the fact that you are capable of bouncing back in sometimes unpredictable situations."

- Thaïs Nivaille, physics student

This article is taken from the "Far away" section of Omalius magazine #38 (September 2025).

"Physics for medical sciences": a reference book to support students throughout their studies

"Physics for medical sciences": a reference book to support students throughout their studies

Initiated and coordinated by Bernard Pireaux (UCLouvain), this collective work - co-authored in particular by Professors Laurent Houssiau and Jim Plumat (UNamur) - offers a reference manual to accompany students of medicine, biomedical sciences and life sciences throughout their course. Designed as a clear, progressive and practical tool, it illustrates just how essential physics is to the understanding of living organisms and to medical practice.

In France, as in Belgium, medical students generally receive little teaching in physics during their course of study. This situation has its roots in history: until the XIXᵉ century, vitalism - a scientific current that originated in the XVIIIᵉ - postulated that living beings were animated by a "vital force" that escaped physical and chemical laws. Gradually, this vision gave way to mechanism, which asserted that even the most complex biological phenomena obeyed the same universal laws as inanimate matter. This transition marked a decisive stage in the history of science, consecrating the fundamental role of physics in the understanding of the living.

It is in this spirit that the book Physics for Medical Sciences, coordinated by Bernard Pireaux, Professor of Physics at the Catholic University of Louvain, is set. A genuine training tool, it brings together all the essential physics concepts useful to students of medicine, life sciences or biomedical sciences.

Clear, ambitious objectives

- Reconcile students with physics by emphasizing its central role in the health sciences.

- Initiate students from the very beginning of their course with the fundamental laws of physics, which are essential to their training.

- In-depth understanding of the physical mechanisms underlying physiological phenomena, right down to their cellular dimensions.

- Modeling more complex physiological systems.

- Support students throughout their course of study, and even beyond.

Over a year of collaborative work

With over 600 pages, this book is much more than a simple syllabus: it aims to be a veritable "bible" of physics applied to the medical sciences. Its writing mobilized several teacher-researchers for over a year.

At UNamur, two physics professors played a key role:

- Jim Plumat, Professor of Physics Emeritus at UNamur, signed chapter 11 devoted to light, the eye and vision.

This book is a reminder that physics is not a cold, abstract science, but an essential key to understanding and caring for the living. It's a genuine invitation to rediscover the beauty of the link between matter, life and medicine.

- Laurent Houssiau, Professor of Physics at UNamur, wrote Chapters 2 and 3 on kinematics and dynamics, and contributed to Chapter 4 on deformable solids.

With 25 years' experience teaching physics to medical students, he explains:

It's a real challenge to teach physics to medical students. I love it and have been doing it every year for 25 years. I know their problems and their questions, which I've learned through contact with them. And every year is different, which also allows me to learn new things.

Based on concrete medical examples and clearly oriented towards medical physics, the book offers a progressive and pragmatic approach. As Laurent Houssiau points out:"This book is perfectly suited to our students of medicine, biomedical sciences and pharmaceutical sciences, as all its authors have written it in the same spirit."

An innovative teaching approach

Designed as a genuine biophysics course, the book is aimed at French and Belgian medical students as well as those enrolled in life and health sciences programs. Each chapter features:

- an introduction to situate and contextualize the subject,

- many exercises and corrected MCQs,

- one or more medical case studies, particularly in physiology.

The project represents a first in the field. With this publication, students finally have a solid reference tool tailored to their needs, to better understand the physical basics essential to medical practice.

Medical studies at UNamur

Manipulating light to revolutionize quantum computing

Manipulating light to revolutionize quantum computing

Two researchers from the University of Namur's Department of Physics, Professor Michaël Lobet and his PhD student Adrien Debacq, are taking a close look at a subject that fascinates the scientific community : superradiance in media with a refractive index close to zero. In an article published this summer in Nature's prestigious journal Light: science & applications, in collaboration with Harvard University (USA), Michigan Technological University (MTU) and Sparrow Quantum, they contribute to the development of quantum computing.

For the past twenty years, a physical phenomenon has been attracting the attention of scientists over the world: superradiance in media with refractive indices close to zero. Among them, Michaël Lobet, professor at the Physics’ Department of UNamur, FNRS research associate and associate at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). “This is one of the major areas I've been studying for ten years now, and for which I was a post-doctoral fellow in Professor Eric Mazur's team at Harvard”, explains Michaël Lobet.

Superradiance, is a phenomenon that has been known for over half a century. It was theorized mathematically as early as 1954 by Robert Dicke, who showed that when elements such as atoms interact, they can synchronize to emit more powerful light. A bit like a choir singing in unison, the sound produced is much louder than each voice taken separately. But for doing this, the emitters must be very close to one another.

A index that changes everything

Scientists have discovered that one element can change everything: when the emitters are immersed in a material with a refractive index close to zero, rather than in vacuum, the position of the emitters is no longer an issue. The refractive index is a quantity that describes the behaviour of light in a material. In an ordinary material, light behaves a little like waves on the sea: it moves forward, forming crests and troughs that shift. But in a near-zero index medium, it's as if the sea becomes perfectly flat, with no waves, and starts moving up and down in a block. Everything moves in unison: the sea becomes uniform, and the wave stretches to infinity.

When the light field becomes more uniform, all the atoms find themselves optically close to each other, even if they are spatially distant. In other words, the "ambient" near-zero refractive index relaxes the strict distance between the atoms' positions, an essential condition for the entanglement of quantum particles. Quantum entanglement corresponds to correlations between particles, essential for the development of information and quantum computers.

From electrodynamics to quantum computing

This is where the promising contribution of a team of researchers from UNamur, Harvard and Michigan Technological University (MTU) comes in, supported by Dr. Larissa Vertchenko, from Danish quantum technology company Sparrow Quantum. Adrien Debacq, FNRS aspirant researcher at the Namur Institute of Structured Matter (NISM) and co-author of the paper, assisted by Harvard PhD student Olivia Mello and Dr Larissa Vertchenko, have together theoretically developed a photonic chip capable of radically improving the range of entanglement between transmitters, up to 17 times greater than in a vacuum. The emitters were made from nitrogen vacancy (NV) diamonds, structures well known in quantum optics.

This is the first time that such a long range has been achieved using a compact system that can be easily implemented in photonic chips

“This paper shows how near-zero refractive index photonics can transition from classical electrodynamics to the quantum regime, since superradiance is intrinsically quantum.”, summarizes Eric Mazur, Professor at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, who has been at the forefront of these innovative materials for the past decade. Entanglement, another purely quantum property, enables the transfer of quantum information, a concept already raised by Einstein in the 1930s as part of his work on quantum mechanics. The present work is part of this continuation, and more generally of the “second quantum revolution”, which aims to build on the fundamental discoveries of Einstein and the other founding fathers of quantum mechanics.

Very concrete applications

This prospect confirms the nascent research in recent years to potentially revolutionary applications: more efficient lasers, more sensitive optical sensors and, above all, faster and ultra-secure telecommunication tools, thanks to quantum computers. Cybersecurity, for example, is about to be revolutionized by these discoveries, guaranteeing message security through physical laws rather than complex calculations.

Preserving the high degree of entanglement on chip over longer ranges may raise the possibility of multipartite entanglement involving many qubits useful for e.g., the construction of cluster states—important resource for universal one-way quantum computing—as well as large-area distributed quantum computing and quantum communication networks that may offer drastic increase on the computational and channel capacity.

Together with Dr. Seth Nelson, Güney has helped to study the dynamic response of the quantum system in the presence of a pump laser beam.

The challenge for future research is to transform this theoretical project, combining analytical models and numerical simulations, into concrete experimental realizations. The aim is to get a little closer to practical quantum systems, which fit into dimensions as small as the thickness of a human hair. Who knows, maybe one day we'll have a quantum computer in our pocket?

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank the Department of Physics and the NISM Institute, the FNRS for funding the research mandates of Michaël Lobet and Adrien Debacq, and the PTCI technology platform, whose supercomputers made this study possible, as well as for funding in part by the United States Army Research Office under MURI grant (W911NF2420195).

Agenda

Public defense of doctoral thesis in physical sciences - Emile Ducreux

Study of water vapor and its deuterated isotopologues in CO2-rich atmospheres

Abstract

In CO2-rich atmospheres such as that of Venus, the study of water vapor requires the use of H2O collision parameters for CO2. However, due to a lack of data, models still use collision parameters for air to estimate the abundance of water vapor in this type of atmosphere. In this thesis, new experimental laboratory measurements of the collision parameters of H2O, HDO, and D2O by CO2 were carried out. These were then used as the basis for dedicated theoretical calculations. Their impact was evaluated using radiative transfer simulations applied to the atmosphere of Venus, under conditions close to those of future observations by the European EnVision mission. The results clearly show that using collision parameters for air instead of CO2 can lead to an overestimation of nearly 40% of the abundance of water vapor in the mesosphere and to inversion difficulties in the troposphere. This work thus provides essential elements for improving the spectral analysis of CO2-rich atmospheres.

Jury

- Dr. Ha TRAN (Sorbonne University), Chair

- Prof. Muriel LEPÈRE (University of Namur), Secretary

- Dr. Emmanuel MARCQ (University of Versailles)

- Dr. David JACQUEMART (Sorbonne University)

- Dr. Laurence RÉGALIA (University of Reims)

- Dr. Séverine ROBERT (Royal Institute for Space Aeronomy, Belgium)

Women in Science 2026 | 6th edition

This annual event aims to promote women's and girls' access to science and technology and their full and equal participation. It highlights the important role of women in the scientific community and provides an excellent opportunity to encourage and promote equal opportunities for all genders in science and technology.

Our keynote speakers for 2026 are Professor Roosmarijn Vandenbroucke (Ghent University) and Professor Nelly Litvak (Eindhoven University of Technology).

IBAF Conference 2026

Sixteen years after hosting the 2010 edition, UNamur is delighted to revive this scientific tradition and welcome the 11th edition of the Rencontres Ion Beam Applications Francophones (IBAF). This edition will be organized by scientists from the UNamur Physics Department who are active in the fields of materials science, biophysics, and interdisciplinary applications of ion beams.

The IBAF Meetings have been organized since 2003, every two years since 2008, by the Ion Beams Division of the French Vacuum Society (SFV), the oldest national vacuum society in the world, which celebrated its 80th anniversary in 2025.

As in previous editions, IBAF 2026 will offer a rich and varied program with guest lectures, oral and poster presentations, and technical sessions. All this will be complemented by an industrial presence to promote exchanges between research and innovation.

The conference will cover a wide range of topics, from ion beam instruments and techniques to the physics of ion-matter interactions, including the analysis and modification of materials, applications in the life sciences, earth and environmental sciences, and heritage sciences.