Chemistry is par excellence the science of transforming matter, and as such lies at the crossroads between the physical sciences and mathematics on the one hand, and the life sciences, earth sciences and materials sciences on the other. State-of-the-art laboratories, led by world-renowned researchers, are dedicated to a wide range of fields, from organic chemistry to materials chemistry, analytical chemistry and theoretical chemistry.

Find out more about the Chemistry Department

Spotlight

News

Producing "green" hydrogen from water from the Meuse River? It's now possible!

Producing "green" hydrogen from water from the Meuse River? It's now possible!

At UNamur, research is not confined to laboratories. From physics to political science, robotics, biodiversity, law, AI, and health, researchers collaborate daily with numerous stakeholders in society. The goal? Transform ideas into concrete solutions to address current challenges.

Focus #2 | What if our rivers became a source of clean energy for the future?

An international team of chemistry researchers, led by Dr. Laroussi Chaabane and Prof. Bao-Lian Su, has just demonstrated that it is possible to produce "green" hydrogen using natural water and sunlight. These findings have been published in the prestigious Chemical Engineering Journal.

When sunlight becomes a source of clean energy

Faced with climate change, pollution, and energy shortages, the search for alternatives to fossil fuels has become a global priority in order to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Among the solutions being considered, green hydrogen appears to be a particularly promising energy carrier: it has a high energy density and can be produced without greenhouse gas emissions. Today, most of the world's hydrogen (around 87 million tons produced in 2020) is obtained through costly and polluting electrochemical processes, mainly used by the chemical industry or fuel cells. Hence the major interest in more sustainable methods.

Water photocatalysis: the "Holy Grail" of chemistry

Producing hydrogen and oxygen directly from water using light, a process known as photocatalysis of water, is often referred to as the "Holy Grail of chemistry" because it is so complex to master. At the University of Namur, researchers at the Laboratory of Inorganic Materials Chemistry (CMI), part of the Nanomaterials Chemistry Unit (UCNANO) and the Namur Institute of Structured Matter (NISM), have taken a decisive step forward. They have demonstrated that it is possible to use natural water, and no longer just ultrapure water, to produce green hydrogen under the action of sunlight.

The core of the process is based on an innovative photocatalyst, which acts as a kind of "chemical pair of scissors" capable of splitting water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen—an area in which the CMI laboratory has recognized expertise.

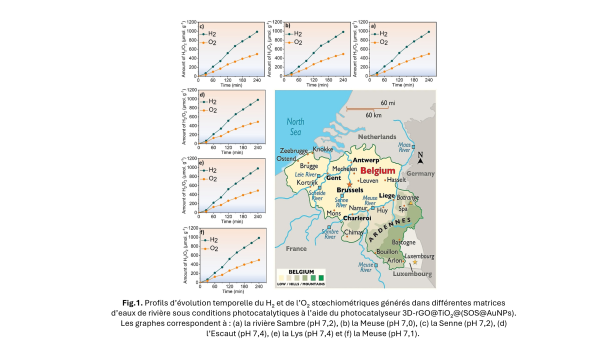

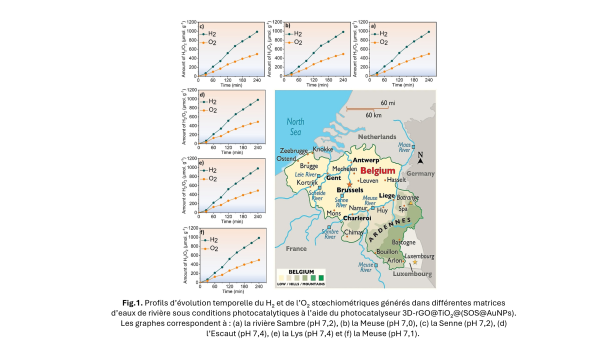

A 3D photocatalyst based on graphene and gold

The new material developed is a three-dimensional (3D) photocatalyst based on titanium oxide, graphene, and gold nanoparticles. This 3D architecture allows for better light absorption and more efficient generation of free electrons, which are essential for triggering the water dissociation reaction. One of the main challenges lies in the use of natural water, which contains minerals, salts, and organic compounds that can disrupt the process. To address this challenge, the researchers tested their device with water from several Belgian rivers: the Meuse, the Sambre, the Scheldt, and the Yser.

A remarkable result and a first in Belgium!

The performance achieved is almost equivalent to that measured with pure water.

This is a first in Belgium, opening up concrete prospects for the sustainable use of local natural resources!

The full article, "Synergistic four physical phenomena in a 3D photocatalyst for unprecedented overall water splitting," is available in open access.

International recognition

This scientific breakthrough also earned Dr. Laroussi Chaabane the award for best poster at the 4th International Colloids Conference (San Sebastián, Spain, July 2025), highlighting the impact and originality of this work.

An international research team

- University of Namur, Faculty of Sciences, UCNANO, Laboratory of Inorganic Materials Chemistry (CMI) and Namur Institute of Structured Matter (NISM), Belgium | Principal Investigator (PI) | Professor Bao Lian SU; Postdoctoral Researcher | Dr. Laroussi Chaabane

- Institute of Organic Chemistry, Phytochemistry Center, Academy of Sciences, Bulgaria

- Department of Organic Chemistry (MSc), Loyola Academy, India

- Free University of Brussels (ULB) and Flanders Make, Department of Applied Physics and Photonics, Brussels Photonics, Belgium

- University of Quebec in Montreal (UQAM), Department of Chemistry, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

- National Institute for Scientific Research - Energy Materials Telecommunications Center (INRS-EMT), Varennes, Quebec, Canada

- Wuhan University of Technology, National Laboratory for Advanced Technologies in Materials Synthesis and Processing, China

What next?

At this stage, the study constitutes proof of concept demonstrating the feasibility of the process. It illustrates the excellence of chemical engineering and nanomaterials research at UNamur, as well as its potential for sustainable energy applications. A new study is underway to evaluate the performance of the process with seawater, a key step towards large-scale green hydrogen production.

State-of-the-art equipment

The analyses carried out were made possible thanks to the equipment available at UNamur's Physico-Chemical Characterization (PC²), Electron Microscopy, and Material Synthesis, Irradiation, and Analysis (SIAM) technology platforms. UNamur's technology platforms house state-of-the-art equipment and are accessible to the scientific community as well as to industries and companies.

The authors would like to thank the Wallonia Public Service (SPW) for its ongoing commitment to scientific research and innovation in Wallonia, enabling UNamur to develop technological solutions with a significant societal and environmental impact.

From fundamental to applied research, UNamur demonstrates every day that research is a driver of transformation. Thanks to the commitment of its researchers, the support of its partners from all walks of life, funders, industrial partners, and a solid ecosystem of valorization, UNamur actively participates in shaping a society that is open to the world, more innovative, more responsible, and more sustainable.

To go further

This article complements our publication "Research and innovation: major assets for the industrial sector" taken from the Issues section of Omalius magazine #39 (December 2025).

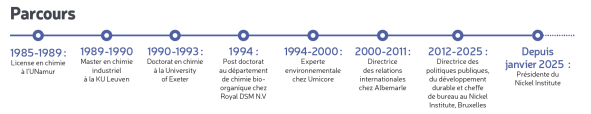

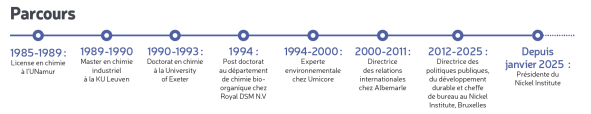

Véronique Steukers, President of the Nickel Institute

Véronique Steukers, President of the Nickel Institute

A chemist by training, Véronique Steukers is now the first woman to head the global organization of nickel producers, the Nickel Institute. Her career path has taken her far from the laboratory and into the heart of an industry facing significant environmental, industrial, and social challenges. We meet her.

What makes nickel so essential today?

Nickel is a surprisingly versatile metal, valued for its strength and durability. This explains its presence in many everyday applications. It has been used for over 100 years in the manufacture of stainless steel, which can be found everywhere in our kitchens, particularly in sinks and cutlery. Nickel makes these utensils highly durable and more resistant to corrosion, particularly from household products. It is also found in certain infrastructures. The Atomium, for example, was completely covered with a layer of nickel-containing stainless steel after its original coating had aged. This guarantees several decades of resistance without degradation. Nickel is also essential for electric car batteries because it improves their energy density, as well as for many other renewable energy technologies. Finally, it is one of the most recycled metals and its importance is set to grow with the increasing return of end-of-life batteries.

What is the role of the Nickel Institute?

The Nickel Institute is a global organization based in Canada with offices on several continents. Its main mission is to promote responsible nickel sourcing and support the sustainable development of this industry. To this end, we have three complementary departments. The first, scientific, is composed of toxicologists specializing in human and environmental health, as well as a prevention advisor responsible for worker protection. The second focuses on public policy and sustainability by monitoring developments in international regulations. It develops methodologies, particularly for measuring carbon footprints. Finally, the third is dedicated to market development and ensures that the various applications of nickel are better known and that markets remain open globally.

You have just been appointed president of the Nickel Institute. What does this appointment mean for your career as a chemist?

It's a role I really wanted to achieve in my career. After studying at UNamur, spending a year studying industrial chemistry in Leuven, completing a PhD in England and a post-doctorate in the Netherlands, I no longer practiced chemistry in a laboratory, but my training has always accompanied my career. It gave me an analytical and critical mind, an understanding of chemical substances, their properties, and industrial processes. This has enabled me to communicate effectively with authorities and stakeholders throughout my career. I often explain that studying chemistry does not only lead to a career in the laboratory. It opens many doors and gives access to a multitude of career paths.

What environmental and societal challenges await the nickel industry?

The stakes are high, especially because this metal is essential to the energy transition. It is found in many climate-related technologies, such as electric car batteries, hydroelectricity, and wind turbines. But nickel remains a mining product, and its production is mainly located in developing countries where the environment, working conditions, and local communities are not always a priority. That is why the Nickel Institute works closely with authorities, companies, and other stakeholders to improve understanding of nickel and its risks. The goal is to ensure that those who produce or handle this metal are aware of best practices for managing the risks associated with extraction, production, and industrial use. The challenge, therefore, remains to guide the industry toward more responsible and sustainable practices.

What do you remember most about your time at UNamur?

I loved my years at UNamur. I am Flemish, and many of my friends did not understand why I chose Namur over Leuven, but I have never regretted it. The atmosphere was very friendly, and the professors and teaching assistants were very welcoming. So much so that we are still in touch, forty years after our first year studying chemistry!

Is there a particular memory you would like to share?

One of my fondest memories is the series of concerts we organized at the Arsenal for two years in a row. I played the piano and had the opportunity to perform a piece for four hands with Professor Jean-Marie André, as well as a trio with two other professors. It was something that came very naturally in Namur, thanks to the small size of the university, where everyone knew each other. I'm not sure I would have found that same closeness anywhere else.

What advice would you give to future chemists?

Don't hesitate! Studying chemistry opens many doors. Of course, you need to have a scientific mind, but it's a course of study that allows you to develop skills that are useful in many professions. I would also advise placing real importance on languages. In Belgium, mastering several languages is an essential asset for advancing in industry. I also notice that there are many more opportunities for women in scientific careers than there used to be. At the beginning of my professional life, I was often the only woman in the room, but today teams are much more mixed, even in heavy industries such as metals. The fact that I became the first female president of the Nickel Institute is quite encouraging.

This article is taken from the "Alumni" section of Omalius magazine #39 (December 2025).

Did you know?

February 11 is International Day of Women and Girls in Science. To mark the occasion, UNamur is organizing the sixth edition of its Women in Science conference. This annual event aims to promote women's and girls' access to science and technology and their full and equal participation. It highlights the important role of women in the scientific community and is an excellent opportunity to encourage and promote equal opportunities for all genders in science and technology.

10 years of UNamur - STÛV collaboration: a lever for innovation, attractiveness and excellence

10 years of UNamur - STÛV collaboration: a lever for innovation, attractiveness and excellence

The University of Namur and STÛV, a Namur-based company specializing in wood and pellet heating solutions, are celebrating ten years of fruitful collaboration. This partnership illustrates the importance of synergies between academia and industry to improve competitiveness and meet environmental challenges.

For over 30 years, UNamur, via its Chemistry of Inorganic Materials Laboratory (CMI) headed by Professor Bao-Lian Su, has excelled in fundamental research into catalytic solutions capable of "cleaning" air and water. In 2014, STÛV approached this expertise to design a sustainable, low-cost smoke purification system for wood-burning stoves, in anticipation of the tightening of European standards.

The R-PUR project: a decisive first step

From this meeting was born the R-PUR applied research project, funded by the Walloon Region and the European Union as part of the Beware program, led by Tarek Barakat (UNamur - CMI). Between 2014 and 2017, an innovative catalytic filter was thus developed within the laboratory, in close collaboration with STÛV.

From 2018 to 2024, the technologies patented by STÛV and UNamur and the pollutant measurement equipment were gradually transferred to STÛV, at the same time as Win4Spin-off and Proof of Concept funding enabled technological and commercial maturities to be increased to meet market needs. These steps led to laying the foundations for a new Business Unit at STÛV, with the hiring of Tarek Barakat as Project Manager, and raising investments to produce the catalytic filters.

What about tomorrow? Towards zero-emission combustion

The UNamur-STÛV collaboration continues today with the Win4Doc (doctorate in business) DeCOVskite project, led by PhD student Louis Garin (UNamur - CMI) and supervised by Tarek Barakat. Objectives:

- Develop a second generation of catalysts to completely reduce fine particle emissions.

- Limit the use of precious metals.

- Sustain biomass combustion and make STÛV the world leader in zero-emission stoves.

A winning partnership for the region

This collaboration has enabled:

- The acquisition and transfer of know-how and equipment between UNamur and STÛV to validate results under industrial conditions.

- The organization of multidisciplinary workshops, such as the one on October 14, promoting the sharing of expertise around biomass combustion and sustainable development.

Success-Story: interviews and testimonials

At the end of October, members of UNamur and STÛV came together to take part in a workshop organized by UNamur's Research Administration and STÛV. The aim? To highlight the benefits of collaborative research between companies and universities on subjects ranging from energy, the environment, profitability, ethics and regulation to sustainable development. The two partners discussed their collaboration, expertise and development prospects.

Discover the details of this success story in this video :

DCF, a molecular weapon against bacterial defenses

DCF, a molecular weapon against bacterial defenses

At a time when bacterial resistance to antibiotics is a public health problem, Professor Stéphane Vincent's team is currently developing dynamic constitutional frameworks (Dynamic Constitutional Frameworks, DCF): a molecular system that would be able to break down certain resistances and thus deliver antibiotics as close as possible to pathogens.

Scientific discoveries are like great stories: they often begin with an encounter. Nearly 20 years ago, Professor Stéphane Vincent of UNamur's Laboratoire de Chimie Bio-Organique, then a young sugar chemist, was in search of something new. During a post-doctorate in Strasbourg, France, in the laboratory of Jean-Marie Lehn, winner of the 1987 Nobel Prize in Chemistry and a specialist in supramolecular chemistry, he befriended another post-doctoral fellow: the Romanian Mihail Barboiu, now a CNRS researcher in Montpellier.

."Research carried out between Montpellier and Strasbourg has given rise to what we call Dynamic Constitutional Frameworks", reveals Stéphane Vincent. "These are molecules that are constantly assembling and disassembling, which gives them interesting properties. Weakly toxic to animal and human cells, DCFs can interact with essential cell components, such as proteins or DNA."

Soon before the Covid-19 pandemic, at a scientific congress, Mihail Barboiu showed Stéphane Vincent the results of his experiments. "He was using DCFs as a kind of transporter, to bring genes (DNA or RNA fragments) into a cell", recalls the chemist. "I then realized that DCFs were positively-charged molecules and readily adapted to DNA, which is negatively-charged. This gave me the idea of using them against bacteria, in the same way as certain antibiotics, which are also positively charged."

An antibacterial turnaround

The two researchers then established an initial research project, with a thesis funded in cotutelle by UNamur, which culminated in 2021 in the publication of the first results showing the antibacterial activity of DCFs. "At the time, I was already working on antibacterial approaches, particularly against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a major pathogen that forms biofilms", explains Stéphane Vincent.

To combat antiseptics and antibiotics, bacteria proceed in several ways. In addition to developing mechanisms to block the functioning of antibiotics, they are able to aggregate or dock themselves to a surface, for example that of a medical implant, and cover themselves with a complex tangle of all sorts of molecules. The latter, known as biofilm, protects the bacteria from external aggression. These biofilms are a major public health problem, as they enable bacteria to survive even the most powerful antibiotics and are notably the cause of nosocomial diseases, infections contracted during a stay in a healthcare establishment.

"We have shown that certain DCFs are both capable of inhibiting biofilm production, but also of weakening them, thereby exposing bacteria to their environment", summarizes Stéphane Vincent.

The TADAM project, a European alliance!

Bolstered by these results and thanks to C2W, a "very competitive"European program that funds post-doctorates, Stéphane Vincent invited Dmytro Strilets, a Ukrainian chemist who had just completed his thesis under the supervision of Mihail Barboiu, to work in his laboratory on DCFs. The project, called TADAM and carried out in collaboration with researchers Tom Coenye of UGent and Charles Van der Henst of the VUB, then focused on the antibacterial and antibiofilm potential of DCFs against Acinetobacter baumannii, a bacterium which, along with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, is on the list of pathogens of greatest concern defined by the World Health Organization (WHO).

The TADAM project is based on an ingenious assembly: DCFs are associated with special molecules known as pillarenes. The latter form a sort of cage around a proven antibiotic molecule, levofloxacin, thus improving its bioavailability and stability. The DCFs then have the role of inhibiting and disintegrating the biofilm, to enable the pillarenes to deliver their antibiotic directly to the bacteria thus exposed.

The results obtained by Stéphane Vincent's team are spectacular: the DCF-pillararene-antibiotic assembly is up to four times more effective than the antibiotic used alone! Noting that little work had yet been done on the antibiotic effect of these new molecules, the researchers decided to protect their invention by filing a joint patent, before going any further.

For everything still remains to be done. Firstly, because despite more than convincing results, how the assembly works is still obscure. "All the study of the mechanism of action has yet to be done, says Stéphane Vincent. "How is the antibiotic arranged in the pillararene cage? Why do DCFs have antibiofilm activity? How do DCFs and pillararenes fit together? All these questions are important, not only to understand our results, but also to eventually develop new generations of molecules."

And on this point, Stéphane Vincent wants to be particularly cautious. "We all dream, of course, of a universal molecule that will work on all pathogens, but we have to be humble, he pauses. "I've been working with biologists for many years, and I know that biological reality is infinitely more complex than our laboratory conditions. But it's because our results are so encouraging that we must persevere down this path."

The chemist already has several leads: "We're going to test the molecules on bacteria"circulating"suspended in a liquid, which behave very differently. And then we're also going to work on clinical isolates of pathogenic bacteria, to get a little closer to the real conditions under which these biofilms form."

Dmytro Strilets has just received a Chargé de Recherche mandate from the FNRS to develop second-generation DCFs and study their mode of action. The TADAM project has received funding from the University of Namur and the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement n°101034383.

This article is taken from the "Eureka" section of Omalius magazine #38 (September 2025).

Producing "green" hydrogen from water from the Meuse River? It's now possible!

Producing "green" hydrogen from water from the Meuse River? It's now possible!

At UNamur, research is not confined to laboratories. From physics to political science, robotics, biodiversity, law, AI, and health, researchers collaborate daily with numerous stakeholders in society. The goal? Transform ideas into concrete solutions to address current challenges.

Focus #2 | What if our rivers became a source of clean energy for the future?

An international team of chemistry researchers, led by Dr. Laroussi Chaabane and Prof. Bao-Lian Su, has just demonstrated that it is possible to produce "green" hydrogen using natural water and sunlight. These findings have been published in the prestigious Chemical Engineering Journal.

When sunlight becomes a source of clean energy

Faced with climate change, pollution, and energy shortages, the search for alternatives to fossil fuels has become a global priority in order to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Among the solutions being considered, green hydrogen appears to be a particularly promising energy carrier: it has a high energy density and can be produced without greenhouse gas emissions. Today, most of the world's hydrogen (around 87 million tons produced in 2020) is obtained through costly and polluting electrochemical processes, mainly used by the chemical industry or fuel cells. Hence the major interest in more sustainable methods.

Water photocatalysis: the "Holy Grail" of chemistry

Producing hydrogen and oxygen directly from water using light, a process known as photocatalysis of water, is often referred to as the "Holy Grail of chemistry" because it is so complex to master. At the University of Namur, researchers at the Laboratory of Inorganic Materials Chemistry (CMI), part of the Nanomaterials Chemistry Unit (UCNANO) and the Namur Institute of Structured Matter (NISM), have taken a decisive step forward. They have demonstrated that it is possible to use natural water, and no longer just ultrapure water, to produce green hydrogen under the action of sunlight.

The core of the process is based on an innovative photocatalyst, which acts as a kind of "chemical pair of scissors" capable of splitting water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen—an area in which the CMI laboratory has recognized expertise.

A 3D photocatalyst based on graphene and gold

The new material developed is a three-dimensional (3D) photocatalyst based on titanium oxide, graphene, and gold nanoparticles. This 3D architecture allows for better light absorption and more efficient generation of free electrons, which are essential for triggering the water dissociation reaction. One of the main challenges lies in the use of natural water, which contains minerals, salts, and organic compounds that can disrupt the process. To address this challenge, the researchers tested their device with water from several Belgian rivers: the Meuse, the Sambre, the Scheldt, and the Yser.

A remarkable result and a first in Belgium!

The performance achieved is almost equivalent to that measured with pure water.

This is a first in Belgium, opening up concrete prospects for the sustainable use of local natural resources!

The full article, "Synergistic four physical phenomena in a 3D photocatalyst for unprecedented overall water splitting," is available in open access.

International recognition

This scientific breakthrough also earned Dr. Laroussi Chaabane the award for best poster at the 4th International Colloids Conference (San Sebastián, Spain, July 2025), highlighting the impact and originality of this work.

An international research team

- University of Namur, Faculty of Sciences, UCNANO, Laboratory of Inorganic Materials Chemistry (CMI) and Namur Institute of Structured Matter (NISM), Belgium | Principal Investigator (PI) | Professor Bao Lian SU; Postdoctoral Researcher | Dr. Laroussi Chaabane

- Institute of Organic Chemistry, Phytochemistry Center, Academy of Sciences, Bulgaria

- Department of Organic Chemistry (MSc), Loyola Academy, India

- Free University of Brussels (ULB) and Flanders Make, Department of Applied Physics and Photonics, Brussels Photonics, Belgium

- University of Quebec in Montreal (UQAM), Department of Chemistry, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

- National Institute for Scientific Research - Energy Materials Telecommunications Center (INRS-EMT), Varennes, Quebec, Canada

- Wuhan University of Technology, National Laboratory for Advanced Technologies in Materials Synthesis and Processing, China

What next?

At this stage, the study constitutes proof of concept demonstrating the feasibility of the process. It illustrates the excellence of chemical engineering and nanomaterials research at UNamur, as well as its potential for sustainable energy applications. A new study is underway to evaluate the performance of the process with seawater, a key step towards large-scale green hydrogen production.

State-of-the-art equipment

The analyses carried out were made possible thanks to the equipment available at UNamur's Physico-Chemical Characterization (PC²), Electron Microscopy, and Material Synthesis, Irradiation, and Analysis (SIAM) technology platforms. UNamur's technology platforms house state-of-the-art equipment and are accessible to the scientific community as well as to industries and companies.

The authors would like to thank the Wallonia Public Service (SPW) for its ongoing commitment to scientific research and innovation in Wallonia, enabling UNamur to develop technological solutions with a significant societal and environmental impact.

From fundamental to applied research, UNamur demonstrates every day that research is a driver of transformation. Thanks to the commitment of its researchers, the support of its partners from all walks of life, funders, industrial partners, and a solid ecosystem of valorization, UNamur actively participates in shaping a society that is open to the world, more innovative, more responsible, and more sustainable.

To go further

This article complements our publication "Research and innovation: major assets for the industrial sector" taken from the Issues section of Omalius magazine #39 (December 2025).

Véronique Steukers, President of the Nickel Institute

Véronique Steukers, President of the Nickel Institute

A chemist by training, Véronique Steukers is now the first woman to head the global organization of nickel producers, the Nickel Institute. Her career path has taken her far from the laboratory and into the heart of an industry facing significant environmental, industrial, and social challenges. We meet her.

What makes nickel so essential today?

Nickel is a surprisingly versatile metal, valued for its strength and durability. This explains its presence in many everyday applications. It has been used for over 100 years in the manufacture of stainless steel, which can be found everywhere in our kitchens, particularly in sinks and cutlery. Nickel makes these utensils highly durable and more resistant to corrosion, particularly from household products. It is also found in certain infrastructures. The Atomium, for example, was completely covered with a layer of nickel-containing stainless steel after its original coating had aged. This guarantees several decades of resistance without degradation. Nickel is also essential for electric car batteries because it improves their energy density, as well as for many other renewable energy technologies. Finally, it is one of the most recycled metals and its importance is set to grow with the increasing return of end-of-life batteries.

What is the role of the Nickel Institute?

The Nickel Institute is a global organization based in Canada with offices on several continents. Its main mission is to promote responsible nickel sourcing and support the sustainable development of this industry. To this end, we have three complementary departments. The first, scientific, is composed of toxicologists specializing in human and environmental health, as well as a prevention advisor responsible for worker protection. The second focuses on public policy and sustainability by monitoring developments in international regulations. It develops methodologies, particularly for measuring carbon footprints. Finally, the third is dedicated to market development and ensures that the various applications of nickel are better known and that markets remain open globally.

You have just been appointed president of the Nickel Institute. What does this appointment mean for your career as a chemist?

It's a role I really wanted to achieve in my career. After studying at UNamur, spending a year studying industrial chemistry in Leuven, completing a PhD in England and a post-doctorate in the Netherlands, I no longer practiced chemistry in a laboratory, but my training has always accompanied my career. It gave me an analytical and critical mind, an understanding of chemical substances, their properties, and industrial processes. This has enabled me to communicate effectively with authorities and stakeholders throughout my career. I often explain that studying chemistry does not only lead to a career in the laboratory. It opens many doors and gives access to a multitude of career paths.

What environmental and societal challenges await the nickel industry?

The stakes are high, especially because this metal is essential to the energy transition. It is found in many climate-related technologies, such as electric car batteries, hydroelectricity, and wind turbines. But nickel remains a mining product, and its production is mainly located in developing countries where the environment, working conditions, and local communities are not always a priority. That is why the Nickel Institute works closely with authorities, companies, and other stakeholders to improve understanding of nickel and its risks. The goal is to ensure that those who produce or handle this metal are aware of best practices for managing the risks associated with extraction, production, and industrial use. The challenge, therefore, remains to guide the industry toward more responsible and sustainable practices.

What do you remember most about your time at UNamur?

I loved my years at UNamur. I am Flemish, and many of my friends did not understand why I chose Namur over Leuven, but I have never regretted it. The atmosphere was very friendly, and the professors and teaching assistants were very welcoming. So much so that we are still in touch, forty years after our first year studying chemistry!

Is there a particular memory you would like to share?

One of my fondest memories is the series of concerts we organized at the Arsenal for two years in a row. I played the piano and had the opportunity to perform a piece for four hands with Professor Jean-Marie André, as well as a trio with two other professors. It was something that came very naturally in Namur, thanks to the small size of the university, where everyone knew each other. I'm not sure I would have found that same closeness anywhere else.

What advice would you give to future chemists?

Don't hesitate! Studying chemistry opens many doors. Of course, you need to have a scientific mind, but it's a course of study that allows you to develop skills that are useful in many professions. I would also advise placing real importance on languages. In Belgium, mastering several languages is an essential asset for advancing in industry. I also notice that there are many more opportunities for women in scientific careers than there used to be. At the beginning of my professional life, I was often the only woman in the room, but today teams are much more mixed, even in heavy industries such as metals. The fact that I became the first female president of the Nickel Institute is quite encouraging.

This article is taken from the "Alumni" section of Omalius magazine #39 (December 2025).

Did you know?

February 11 is International Day of Women and Girls in Science. To mark the occasion, UNamur is organizing the sixth edition of its Women in Science conference. This annual event aims to promote women's and girls' access to science and technology and their full and equal participation. It highlights the important role of women in the scientific community and is an excellent opportunity to encourage and promote equal opportunities for all genders in science and technology.

10 years of UNamur - STÛV collaboration: a lever for innovation, attractiveness and excellence

10 years of UNamur - STÛV collaboration: a lever for innovation, attractiveness and excellence

The University of Namur and STÛV, a Namur-based company specializing in wood and pellet heating solutions, are celebrating ten years of fruitful collaboration. This partnership illustrates the importance of synergies between academia and industry to improve competitiveness and meet environmental challenges.

For over 30 years, UNamur, via its Chemistry of Inorganic Materials Laboratory (CMI) headed by Professor Bao-Lian Su, has excelled in fundamental research into catalytic solutions capable of "cleaning" air and water. In 2014, STÛV approached this expertise to design a sustainable, low-cost smoke purification system for wood-burning stoves, in anticipation of the tightening of European standards.

The R-PUR project: a decisive first step

From this meeting was born the R-PUR applied research project, funded by the Walloon Region and the European Union as part of the Beware program, led by Tarek Barakat (UNamur - CMI). Between 2014 and 2017, an innovative catalytic filter was thus developed within the laboratory, in close collaboration with STÛV.

From 2018 to 2024, the technologies patented by STÛV and UNamur and the pollutant measurement equipment were gradually transferred to STÛV, at the same time as Win4Spin-off and Proof of Concept funding enabled technological and commercial maturities to be increased to meet market needs. These steps led to laying the foundations for a new Business Unit at STÛV, with the hiring of Tarek Barakat as Project Manager, and raising investments to produce the catalytic filters.

What about tomorrow? Towards zero-emission combustion

The UNamur-STÛV collaboration continues today with the Win4Doc (doctorate in business) DeCOVskite project, led by PhD student Louis Garin (UNamur - CMI) and supervised by Tarek Barakat. Objectives:

- Develop a second generation of catalysts to completely reduce fine particle emissions.

- Limit the use of precious metals.

- Sustain biomass combustion and make STÛV the world leader in zero-emission stoves.

A winning partnership for the region

This collaboration has enabled:

- The acquisition and transfer of know-how and equipment between UNamur and STÛV to validate results under industrial conditions.

- The organization of multidisciplinary workshops, such as the one on October 14, promoting the sharing of expertise around biomass combustion and sustainable development.

Success-Story: interviews and testimonials

At the end of October, members of UNamur and STÛV came together to take part in a workshop organized by UNamur's Research Administration and STÛV. The aim? To highlight the benefits of collaborative research between companies and universities on subjects ranging from energy, the environment, profitability, ethics and regulation to sustainable development. The two partners discussed their collaboration, expertise and development prospects.

Discover the details of this success story in this video :

DCF, a molecular weapon against bacterial defenses

DCF, a molecular weapon against bacterial defenses

At a time when bacterial resistance to antibiotics is a public health problem, Professor Stéphane Vincent's team is currently developing dynamic constitutional frameworks (Dynamic Constitutional Frameworks, DCF): a molecular system that would be able to break down certain resistances and thus deliver antibiotics as close as possible to pathogens.

Scientific discoveries are like great stories: they often begin with an encounter. Nearly 20 years ago, Professor Stéphane Vincent of UNamur's Laboratoire de Chimie Bio-Organique, then a young sugar chemist, was in search of something new. During a post-doctorate in Strasbourg, France, in the laboratory of Jean-Marie Lehn, winner of the 1987 Nobel Prize in Chemistry and a specialist in supramolecular chemistry, he befriended another post-doctoral fellow: the Romanian Mihail Barboiu, now a CNRS researcher in Montpellier.

."Research carried out between Montpellier and Strasbourg has given rise to what we call Dynamic Constitutional Frameworks", reveals Stéphane Vincent. "These are molecules that are constantly assembling and disassembling, which gives them interesting properties. Weakly toxic to animal and human cells, DCFs can interact with essential cell components, such as proteins or DNA."

Soon before the Covid-19 pandemic, at a scientific congress, Mihail Barboiu showed Stéphane Vincent the results of his experiments. "He was using DCFs as a kind of transporter, to bring genes (DNA or RNA fragments) into a cell", recalls the chemist. "I then realized that DCFs were positively-charged molecules and readily adapted to DNA, which is negatively-charged. This gave me the idea of using them against bacteria, in the same way as certain antibiotics, which are also positively charged."

An antibacterial turnaround

The two researchers then established an initial research project, with a thesis funded in cotutelle by UNamur, which culminated in 2021 in the publication of the first results showing the antibacterial activity of DCFs. "At the time, I was already working on antibacterial approaches, particularly against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a major pathogen that forms biofilms", explains Stéphane Vincent.

To combat antiseptics and antibiotics, bacteria proceed in several ways. In addition to developing mechanisms to block the functioning of antibiotics, they are able to aggregate or dock themselves to a surface, for example that of a medical implant, and cover themselves with a complex tangle of all sorts of molecules. The latter, known as biofilm, protects the bacteria from external aggression. These biofilms are a major public health problem, as they enable bacteria to survive even the most powerful antibiotics and are notably the cause of nosocomial diseases, infections contracted during a stay in a healthcare establishment.

"We have shown that certain DCFs are both capable of inhibiting biofilm production, but also of weakening them, thereby exposing bacteria to their environment", summarizes Stéphane Vincent.

The TADAM project, a European alliance!

Bolstered by these results and thanks to C2W, a "very competitive"European program that funds post-doctorates, Stéphane Vincent invited Dmytro Strilets, a Ukrainian chemist who had just completed his thesis under the supervision of Mihail Barboiu, to work in his laboratory on DCFs. The project, called TADAM and carried out in collaboration with researchers Tom Coenye of UGent and Charles Van der Henst of the VUB, then focused on the antibacterial and antibiofilm potential of DCFs against Acinetobacter baumannii, a bacterium which, along with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, is on the list of pathogens of greatest concern defined by the World Health Organization (WHO).

The TADAM project is based on an ingenious assembly: DCFs are associated with special molecules known as pillarenes. The latter form a sort of cage around a proven antibiotic molecule, levofloxacin, thus improving its bioavailability and stability. The DCFs then have the role of inhibiting and disintegrating the biofilm, to enable the pillarenes to deliver their antibiotic directly to the bacteria thus exposed.

The results obtained by Stéphane Vincent's team are spectacular: the DCF-pillararene-antibiotic assembly is up to four times more effective than the antibiotic used alone! Noting that little work had yet been done on the antibiotic effect of these new molecules, the researchers decided to protect their invention by filing a joint patent, before going any further.

For everything still remains to be done. Firstly, because despite more than convincing results, how the assembly works is still obscure. "All the study of the mechanism of action has yet to be done, says Stéphane Vincent. "How is the antibiotic arranged in the pillararene cage? Why do DCFs have antibiofilm activity? How do DCFs and pillararenes fit together? All these questions are important, not only to understand our results, but also to eventually develop new generations of molecules."

And on this point, Stéphane Vincent wants to be particularly cautious. "We all dream, of course, of a universal molecule that will work on all pathogens, but we have to be humble, he pauses. "I've been working with biologists for many years, and I know that biological reality is infinitely more complex than our laboratory conditions. But it's because our results are so encouraging that we must persevere down this path."

The chemist already has several leads: "We're going to test the molecules on bacteria"circulating"suspended in a liquid, which behave very differently. And then we're also going to work on clinical isolates of pathogenic bacteria, to get a little closer to the real conditions under which these biofilms form."

Dmytro Strilets has just received a Chargé de Recherche mandate from the FNRS to develop second-generation DCFs and study their mode of action. The TADAM project has received funding from the University of Namur and the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement n°101034383.

This article is taken from the "Eureka" section of Omalius magazine #38 (September 2025).

Agenda

15th International Conference on Electroluminescence and Optoelectronic Devices (ICEL 2026)

ICEL is recognized as a leading research conference in the field of organic electroluminescence and devices. This event has been organized, generally every two years, since its inception in Fukuoka, Japan, in 1997, by Professor Tetsuo Tsutsui.

In 2026, the Department of Chemistry and Professors Yoann Olivier and Benoît Champagne are pleased to host this event at the University of Namur.

In line with its predecessors, ICEL 2026 will provide an excellent opportunity for the intellectual and social exchanges that keep our community closely connected. It will bring together participants from all over the world involved in the research, development, and manufacturing of emissive materials. A wide array of subjects will be explored, offering a comprehensive perspective on contemporary advances in these fields. We extend a warm invitation for the dissemination of recent breakthroughs in related topics, with a particular emphasis on fostering the active participation of young and motivated researchers.

We especially expect to cover the following topics:

- Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence emitters

- Radical emitters

- Organometallic complexes

- Perovskites

- Lasing

- Circularly polarized luminescence

- Light emission from exciplexes

- Green- and biophotonics

- Computational modeling of light-emitting materials

All practical information (registration, abstract submission, and accommodation) is available on the ICEL2026 website.